In writing an introduction to this post, I found myself straying unexpectedly into alliteration. This happens sometimes. I decided to run with it.

So, as an aside from our accustomed analysis of antiquity, we’ve assembled an array of artefacts for the the amusement and appreciation of archaeologist and amateur alike. Enjoy!

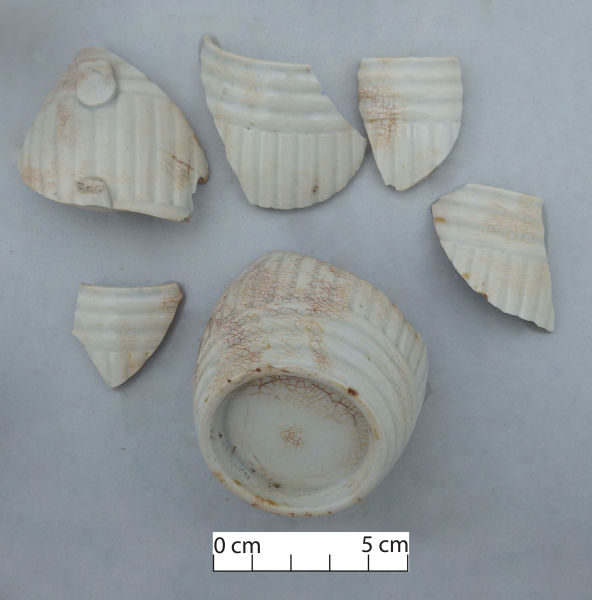

A lovely little milk jug recovered from one of our larger sites on Lichfield Street. We don’t often find jugs like these in such complete condition: we’re far more likely to find just the spout or part of the handle. Image: J. Garland.

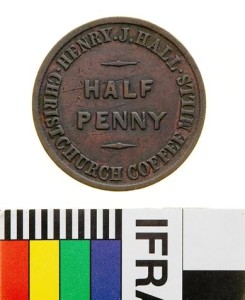

A Christchurch trade token, issued by Hobday and Jobberns, a drapery firm based at Waterloo House on Cashel Street. Tokens like these were used in place of government issued money for much of the late 19th century due to the shortage of actual currency in New Zealand during this period (Thomas & Dale 1950: 42-46). Image: J. Garland.

A blue and white transfer printed saucer featuring three figures meeting under an arch. Unfortunately, no maker’s mark was evident on this piece, meaning we were unable to trace it to its original manufacturer. Image: J. Garland.

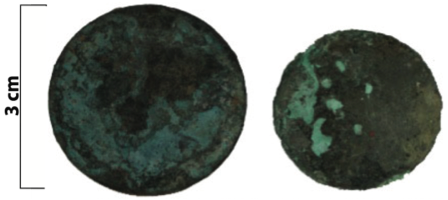

A musket ball! This was a pretty unexpected find: musket balls are not common finds, particularly in the context of 19th century Christchurch. It probably wasn’t used for an actual musket, but may have been intended for a smaller calibre gun. Image: J. Garland.

This ‘Pratt ware’ jar is decorated with a scene from the Crimean war, featuring Sir Harry Jones, a well known British military figure. Sir Harry, who rose to the status of general, commanded the British forces and then the Royal Engineers during the Crimean war, having previously fought in several other campaigns, including one with the Duke of Wellington. Image: J. Garland.

A beautiful gilt decorated and transfer printed candle holder, or ‘chamber stick’, as they were known during the 19th century. The cone feature to the top left of the vessel was there to hold the candle-snuffer, keeping it within easy reach. Image: G. Jackson.

This wee bottle originally contained Rowland’s Macassar Oil, a hair restorative and beautifier. It was first introduced during the late 18th century by Alexander Rowland, a barber (a very expensive barber, apparently) based in St James, London. It was then marketed by his son, Alexander Rowland Junior, who did so to great success (Rowland 2013). Macassar oil was in use throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century and is the origin of the term ‘antimacassar’, referring to the piece of fabric thrown over the top or back of arm chairs. Apparently, antimacassars were developed in response to the oily residue people wearing the oil would leave on furniture. Who knew! Image: J. Garland.

A teacup fragment, on which the image of a monkey examining itself in the mirror is displayed. Because, why not? Image: K. Bone.

A wooden ruler found under the floorboards of a 19th century house in Christchurch, with “McCallums The Timber People” printed on the front. McCallum & Co were an Invercargill based timber company, who were established prior to 1864. By the early 20th century, the company was run by a partnership between William Asher and Archibald McCallum, with branch offices in Dunedin, Gore, Oamaru, Kelso and Winton (Cyclopedia of New Zealand 1905). They appear to have been purchased by Fletcher’s at some point during the 20th century. Image: J. Garland.

A beautiful Alma patterned plate, found on a site on Armagh Street. There isn’t really much to say about this particular plate. I just think it’s pretty. Image: J. Garland.

It can be pretty easy to forget that there was another British monarch between the end of George IV’s reign and the beginning of Queen Victoria’s time on the throne. There’s the Georgian period, then there’s the Victorian period and those seven years between them when William IV was the King of England get sort of forgotten about. This coin, a half-crown, was minted in 1835, during William’s reign, and it is his slightly smiling profile that adorns one side, jaunty hair and all. Image: J. Garland.

The royal bust on this artefact isn’t quite as affable seeming as William IV’s. In fact, if I may say so, the smudges of dirt don’t do anything for the shape of her nose (a bit beak like, isn’t it?). This pipe celebrates Queen Victoria’s Royal Jubilee, which she had two of – one in 1887 (50 years) and one in 1897 (60 years). It’s unclear exactly which one this pipe is referring to. Image: J. Garland.

Jessie Garland

References

Cyclopedia Company Limited, 1905. Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Otago and Southland Provincial Districts]. Cyclopedia Company Ltd., Christchurch. [online] Available at www.nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. [Accessed May 2015]

Rowland, R., 2013. Fifteen Generations of the Rowland Family. [online] Available at www.rowlandgenerations.org. [Accessed May 2015]

Thomas, E. R. & Dale, L. J., 1950. They Made Their Own Money: the Story of Early Canterbury Traders & Their Tokens. Royal Numismatic Society of New Zealand, Canterbury.