“The degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons”

– Fyodor Dostoevsky

One of the challenges faced by any new colony is what to do with the non-conformists, renegades, and criminals. The ideal, of course, is that your new paradise will be carefully designed to have eliminated these undesirable elements. The reality, however, is far from the ideal. The first lock-up in the Canterbury (consisting of three blockhouses) was located in Akaroa, a significant distance away from the growing towns of Christchurch and Lyttelton (Gee 1975: 5). These blockhouses appear to have been used until John Godley arrived on the scene in April 1850 and was appointed as the resident magistrate of Lyttelton (Gee 1875: 7). With his appointment, the location of the lock-ups/gaols moved to the fledgling port-town instead. The earliest gaols in Lyttelton were improvised and, for some enterprising fellows, rather portable. One particularly slapstick story of a runaway gaol involves some opportunistic pranking by the future gaol warden, Edward Seagar:

One night the prisoners in the lock-up, a flimsy, A-frame construction, took up the floor boards, lifted the building and walked away with it. Seagar arranged ropes and stakes in such a way that the escapees unknowingly headed towards the police station further down the hill (Young 2014).

The landing of passengers from the Charlotte Jane, Randolph, Cressy, and Sir George Seymour in Lyttelton c. 1850. Plenty of open space for pranks. Image: Alexander Turnbull Library.

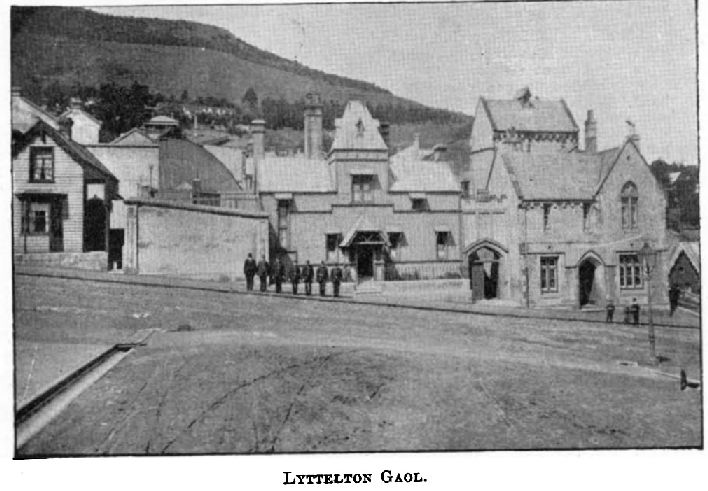

The first permanent gaol buildings in the settlement were constructed between 1851 and c.1857-1861 on Oxford Street, using both hired and prison labour (Gee 1975: 8, 10). Later buildings followed the design of B. W. Mountfort, who also designed the Sunnyside Lunatic Asylum (Heritage New Zealand 2016). The decision to construct a gaol in a small town like Lyttelton may seem odd to us today, but the reasoning was fairly straightforward. Lyttelton was the bigger town at the time and the new buildings replaced the earlier makeshift prisons near the contemporary police station and court (Gee 1975: 10).

The Lyttelton Gaol, date unknown. Image: Cyclopedia Company Limited 1903. A later image of the gaol c. 1900 can be viewed here.

Early conditions in this gaol, according to some commentators, had something of a Dickensian feel:

The early days were those of the cat [of nine tails whip] and the triangle, of the 70lb dragging irons, the days of scanty clothing, poor food, the days when the warder was king (Gee 1975: 2).

Others have argued that, in light of the standards at the time, the treatment of the prisoners was not quite as cruel as it may seem to us today (Gee 1975: 10). Conditions were hampered by one major issue which arose in this early period – the swelling gaol population. This population growth was exacerbated by the incarceration of debtors and the mentally ill. The housing of the mentally ill at the gaol was particularly concerning to many (Young 2014). The young townships of Lyttelton and Christchurch simply did not have the facilities to deal with these patients at the time. To their credit, it was intended that the patients be housed in the new Christchurch Hospital, until there was a furore in response to this plan (Gee 1975: 35). The population pressures eased with the construction of Sunnyside Asylum in 1863, and the opening of the prison in Addington in the 1870s (Gee 1975: 30, 87).

Sunnyside Lunatic Asylum. Image: Te Papa O.034082.

Part of the Addington Prison complex, c. 2005. Image: Wikimedia Commons. The prison is now a backpackers.

The position of the gaol within town life is quite interesting. As illustrated in the image above, the large Gothic style buildings were quite a dominating feature of the town. In addition to this, the prisoners were involved with a number of town works (discussed further below) and services which ensured a high public presence (Heritage New Zealand 2016). These services included a printing shop, a laundrette for the Lyttelton Hospital and Orphanage and the Immigration Department, and a baking contract for the orphanage (Gee 1975: 17). However, one comment from a resident regarding the communities’ view of the gaol (made after the demolition of the gaol in the 1920s) is particularly telling:

We never thought about the gaol. We just knew it was there and that was it. But many people couldn’t have been pleased about it because there are few photographs of it and no paintings as far as I have found (C. Fletcher in Gee 1975: 87).

A rather macabre aspect of the prison, which feels particularly repugnant to us today, is that between 1868 and 1918 seven men convicted of murder were executed at the gaol. This was an aspect of the gaol that was a source of curiosity for some of the younger residents, but of dread for most. One resident stated: “In a little place like Lyttelton the knowledge of an impending execution used to hang like a pall over the whole town” (I. Gray in Gee 1975: 47). It is quite a stretch for me to imagine a community continuing with their daily lives in the anticipation of such an event. Executions appear to have been so entrenched in the town’s psyche that despite the fact that the bell did not toll for the last execution in 1918, many residents insist they remember it ringing (Gee 1975: 47).

A poem by Basil Dowling. The role of the hangman was a necessary part of the justice system, but carried a heavy stigma for the men who did the job. There are a number of cases where officers had to smuggle the hangman in on the eve of the execution to avoid the curiosity and/or anger of the general public.

The archaeological legacy of the prison and prisoners remain visible in many aspects of the town today. All that remains of the gaol itself are concrete retaining walls, a small block of cells, pedestrian pathways and concrete steps. These remains are an important archaeological site, particularly as they are demonstrative of some of the earliest use of concrete in New Zealand (Heritage New Zealand 2016).

The remaining cells and concrete walls of the prison. Image: A. Bulovic, 2013 Peeling Back History.

However, we can also see the influence of the gaol on the Lyttelton settlement through other features of the town. Prisoners sentenced to hard labour were part of gangs put to work on public works, such as road formation and retaining wall construction. In particular, the red volcanic retaining walls constructed during this period have been described as a distinctive part of the townscape. Unfortunately, as with much of Lyttelton’s heritage, a number of these walls have been repaired or replaced after the damage from the earthquakes.

Earthquake damaged walls at the corner of Coleridge Terrace and Dublin Street. Image: M. Hickey, 2015.

The newly constructed concrete wall on Sumner Road, with partial re-facing using the volcanic stone from the demolished wall. The re-facing will occur on as many of the key retaining walls across the town as funding allows. Image: M. Hickey, 2016.

A collapsed wall at 61 St Davids Street. Image: M. Hickey, 2016.

The same wall after deconstruction and reconstruction work (all completed by hand). Image: M. Hickey, 2016.

The port also benefited from convict labour in the form of reclamation construction and wharf building (Gee 1975: 17). Another notable site of works is the fortifications at Ripapa Island, which were constructed in the 1860s and 1870s by the Hard Labour Gang and were even used to house some prisoners (Gee 1975: 22). Prisoners housed on the island reportedly included members of the Parihaka resistance movement in Taranaki in 1880s (Donna R 2014). These men are remembered today during a service on the 5th of November each year and a memorial at Rapaki (Lyttelton Community House Trust 2013).

In many ways, the Lyttelton Gaol was a product of its time; the morality of Victorian Britain, the realities of a new colonial land and the challenges of a growing society. However, the legacy of the gaol should not be limited to a grim spectre of past principles. Prisoners made a considerable contribution to the development of the town through the construction of infrastructure. Despite the recent changes to the townscape, the influence of the gaol remains a visible part of Lyttelton’s heritage.

Megan Hickey

References

Gee, D. 1975. The Devil’s Own Brigade: A History of the Lyttelton Gaol 1860-1920. Wellington: Millwood Press Ltd.