It’s very easy to think of 19th century New Zealand as being a place isolated from the rest of the world. Yet as we research and investigate colonial Christchurch, we are constantly being reminded of the connections that existed between New Zealand and the rest of the British Empire. Most often we see those connections archaeologically through artefacts, but every so often we see them in a different way. Today’s blog is on a Turkish Bathhouse we excavated at the end of last year. When I think of 19th century Christchurch, a Turkish Bathhouse is definitely not the first thing that comes to mind. Yet Turkish Bathhouses became fashionable in Britain in the 1860s and from there spread to the rest of the empire, with Turkish Bathhouses opened in New Zealand in the 1870s (Press 31/12/1874: 2).

The Turkish Bath, or Hammam, is a public bathhouse that is associated with Muslim culture and found across the Islamic world. Hammam have been in existence for over a thousand years and evolved from similar public bathhouses used by the Ancient Romans. The Hammam was both a place to get clean, and a place to socialise and conduct business. The introduction of the Hammam to the British Empire was down to one man: David Urquhart. David Urquhart was a Scottish diplomat and politician who worked in Constantinople (Istanbul) in the 1830s and travelled throughout Europe and the east over his lifetime. In 1850, Urquhart wrote a book, The Pillars of Hercules, based on his travels through Spain and Morocco in 1848. Urquhart dedicates two chapters of his book to bathhouses, describing both the history of the bathhouse and the bathhouse process.

“The operation consists of various parts: first, the seasoning of the body; second, the manipulation of the muscles; third, the peeling of the epidermis; fourth; the soaping, and the patient is then conducted to the bed of repose. These are the five acts of drama. There are three essential apartments in the building: a great hall, or mustaby, open to the outer air; a middle chamber, where the heat is moderate; the inner hall, which is properly the thermae. The first scene is acted in the middle chamber; the next three in the inner chamber, and the last in the outer hall. The time occupied is from two to four hours, and the operation is repeated once a week.”

-Urquhart 1850: 31

To call Urquhart passionate about bathhouses would be an understatement. His chapter on the bathhouse process begins with a very Victorian description of the morality of cleanliness, followed by an extensive description of the bathhouse process. Urquhart bases his description of bathhouses on the Hammam he had visited in Turkey and is quite critical of the Moorish bath he visited on his travels, providing a comparison between the Moorish bathhouse, the Turkish bathhouse, and Roman bathhouses. Urquhart ends his chapter with a very lengthy description of the benefits of introducing bathhouses to Britain. Richard Barter, an Irish physician who established St Ann’s Hydropathic Establishment, read Urquhart’s book and collaborated with him to open Britain’s first Turkish Bath in Ireland in 1856. In 1857 a Turkish Bathhouse opened in Manchester and in 1860 another opened in London. Over the next 150 years, over 600 Turkish Baths were opened in Britain.

I visited a Turkish Bath when I was in Turkey. I didn’t take any photos, but thanks to the magic of the internet I was able to find a picture of the one I went to. It was a few years ago now, but I remember both enjoying the experience and finding it a wee bit strange being washed by a stranger. My experience started with a sauna. Following that we went to this room where we were scrubbed and washed. We then had a massage and ended with face masks. All in all, it was relatively similar to what Urquhart describes – particularly the “peeling of the epidermis” and the “soaping”. Image: Tripadvisor.

In August 1884, John Charles Fisher and Duncan Beamont Wallis leased a section of land on Cashel Street and constructed a Turkish Bathhouse. Construction was completed in October 1884 and the baths were open for business by the 21st of October. While Fisher and Wallis constructed the baths, they did not operate it for long and management was taken over by W. Dation in January of 1885. Dation himself did not operate the baths for long, and by June of 1885 was advertising the sale of a large amount of the bath’s furniture and fittings (suggesting he may have had financial difficulties).

Robert Hall announced he was taking over the proprietorship of the Oriental Turkish Baths on the 1st July 1885. He described the premises at this time as being “Now in First Class Order”, having been “Fitted and Furnished in the very Best Style”, which suggests that Hall replaced much of the furniture and fittings that had been sold by Dation (Star 29/6/1885: 2). He undertook various alterations and repairs to the premises during his proprietorship, adding a third hot room that could reach 200 degrees Fahrenheit. Hall was the proprietor of the bathhouse until 1905, when the business was taken over by Messrs. Young and Co., who operated the bathhouse until the property was sold in the 1920s (Trendafilov et al. 2021).

Photograph printed in 1902, showing the street frontage of Hall’s Oriental Turkish Baths in Cashel Street. Image: Davie, 1902: 304.

An advertisement from 1886, advertising the baths. Image: Star, 27/12/1886: 2.

The construction of the bathhouse was clearly of interest to the residents of Christchurch, and a thorough description of the building was relayed in the newspapers of the time:

The building will be of brick, and will cover a ground area of 60ft by 33ft. In the front are the hair-dressing rooms. A passage runs right through the building from front to back; to the right of this from the entrance are six chambers for hot, cold, and shower baths. On the left are the rooms for the special feature of the establishment – the Turkish baths. The person wishing to enjoy the Oriental luxury will first enter one of the dressing-rooms, of which there are eight, very neatly fitted up; he then passes to the first hot room, at which the temperature is maintained at about 125 deg Fah., and having become accustomed to this, he is prepared to pass to the hotter chamber, of 150 deg on an average. Both these hot rooms are of the same size — 12ft by 9ft 6in, floored with red and white tiles, and plastered; they are heated by hot-air flues passing round them, and connected with a furnace at the back. Special attention will be paid to ventilation, not only in these rooms, but in all connected with the baths. Disc ventilators in the walls and ceiling, that can be opened or closed at will, are the description made use of for the purpose. After he has had enough of the hot-air process, the visitor will pass to the shampooing room, in which is the “needle bath.” The operation of this is to throw from a number of small jets sprays of water gradually decreasing from warm to cold, thus preventing the danger to the bather of suffering a chill after he has finished his Turkish bath. Sulphur and vapour baths are also provided in the shampooing room, on leaving which the visitor pushes aside a crimson curtain and finds himself in the “cooling room,” a large, handsomely furnished apartment, in which files of the illustrated and other papers are kept, and where one can enjoy the dolce far niente till he feels disposed to return to the dressing-room. All the rooms, except those in front, are lighted by skylights (Lyttelton Times 15/8/1884: 6).

Sadly, the original bathhouse was long gone when we excavated the site last year. However, we found a couple of features that we were able to associate with the bathhouse, which was most exciting. One was a large brick structure, found at a depth of 750 mm. The feature was a trapezoid shaped lined brick pit, 3.4 m long and 1.4 m, which was located within the footprint of the bathhouse and was interpreted as being one of the baths.

The bath feature, first exposed by the digger. The feature didn’t look like much when it was first uncovered, but careful excavation revealed something interesting. Image: A. Trendafilov.

The bath emerges. Image: A. Trendafilov.

Angel does some phenomenology and puts himself in the place of a visitor to the baths. Image: site contractor.

We suspect that the bath was constructed as part of the purpose built building and was probably sunk into the ground which has led to it surviving. Interestingly, as Angel was excavating the feature he found several bits of radiator, along with a lead pipe with evenly distributed holes along the side. The 1884 description of the new bath house mentions that there were two hot chambers available, with temperatures of 125° Fahrenheit (51° Celsius) and 150° Fahrenheit (65° Celsius), connected to a furnace at the back of the building. It is probable that the radiators were used to transfer the heat to these chambers, either through the use of steam or hot water. The small lead pipe found in the feature may have been part of the ‘needle bath’ described in the same account: “the operation of this is to throw from a number of small jets sprays of water gradually decreasing from hot to cold” (Lyttelton Times 15/8/1884: 6). It is highly likely that the evenly distributed holes, which measured six mm in diameter and were spaced at intervals of approximately 50 mm, in the pipe are those small jet sprays described in the article.

The radiators were clustered down on end of the bath. Image: A. Trendafilov.

The radiator pipes. Image: A. Trendafilov.

The lead pipe with evenly spaced holes. Image: J. Garland.

We also found several coffee and chicory bottles in the feature, and overall coffee and chicory bottles made up 13% of the total glass assemblage (normally they might make up around 1% of a total glass assemblage). The ‘Oriental Turkish Bath House’ served tea and coffee to customers, with an article from September 1884 stating that “the room in which, what is, perhaps, the most pleasant part of the process takes place is a large, handsomely furnished apartment, with Brussels carpet on the floor and luxurious couches and chairs around the walls…and small tables disposed in various parts of the room can be used either as card tables or to bear the cup of tea or coffee presented to the visitor” (Star 21/10/1884: 3). It is however surprising that they may have been serving coffee and chicory or coffee extract, both of which can be considered substitutes for ground coffee or the equivalent of ‘instant’ coffee. Their use in the 19th century is often associated with economic hardship and coffee shortages, particularly in Napoleonic France and Civil War era North America (Smith 1996; Smith 2014). It may be that the Turkish Bath House was using coffee substitutes as a matter of taste preference, but it may also have been that they were economical in what they were serving to visitors.

One of the coffee and chicory bottles found in the feature. The bottle was embossed with the mark of Thomas Symington and Co., an Edinburgh based beverage manufacturer. Symington’s Coffee and Chicory, a blended coffee beverage, is relatively common on archaeological sites in New Zealand dating from the 1880s onwards. Image J. Garland.

We also found this Cyprus patterned ewer, which was likely used in the bathhouse. The ewer was made by Thomas G. Booth, a Staffordshire potter who operated the Church Bank Pottery in Tunstall between 1876 and 1883 (Godden 1991: 86). The date of manufacture for this vessel pre-dates the construction of the Turkish Baths, but ceramic vessels during the 19th century often had uselives of up to 15-20 years (Adams 2003), which would overlap with the construction and use of the Turkish Baths. It may be that the name of the pattern decorating this vessel, the Cyprus Pattern, was a deliberate choice on the part of the owners of the baths, as a nod to the geographical location of Cyprus, south of Turkey in the Mediterranean Sea, but it may also have been a coincidence in which the visual appearance of the pattern determined the choice of its use in the Turkish Baths. Image: J. Garland.

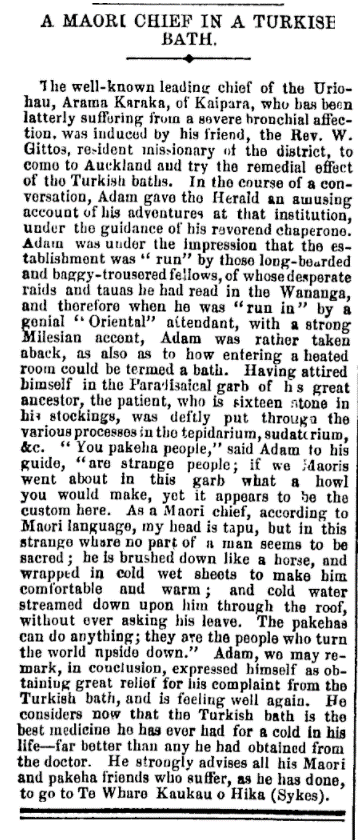

Hall’s Oriental Turkish Bath provides a fascinating insight into the cultural melting pot of the British Empire. It’s interesting to see the introduction of Turkish Baths into Britain in the 1850s, and from there, as they became fashionable, spreading through the Empire to reach New Zealand in the 1870s. A Turkish Bath was opened in Dunedin in 1874 (Press 31/12/1874: 2), one in Auckland by 1877 (New Zealand Herald 14/07/1877: 4) while an earlier bath opened on High Street in Christchurch in 1878 (Press 22/02/1878: 1). The collision of different cultures that resulted in the spread of ideas and practices across the empire is perhaps best illustrated in the below article.

A collision of culture. Image: Evening Post 12/07/1879: 3.

Clara Watson, Jessie Garland, Lydia Mearns

References

Davie, Mort., 1902. Tourists’ Guide to Canterbury. P. A. Herman. Christchurch Press Company Limited.

Godden, G., 1991. Encyclopaedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks. Crown Publishers, New York.

Lyttelton Times, 1851-1914. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/.

New Zealand Herald, 1863-1945. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Press, 1861-1945. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Smith, S. D., 1996. “Accounting for Taste: British Coffee Consumption in Historical Perspective”, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 27: 2, pp. 183-214.

Smith, A. K., 2014. “The History of the Coffee Chicory Mix That New Orleans Made It’s Own”, Smithsonian Magazine. [online] Available at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/chicory-coffee-mix-new-orleans-made-own-comes-180949950/ [Accessed March 2021].

Star, 1868-1920. [online] Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/.

Trendafilov, A., Mearns, L., Garland, J. 212 Cashel Street, Christchurch (Superlot 6c): Final report for archaeological investigations under HNZPT authority 2020/811eq. Unpublished report for Fletcher Residential Living.

Urquhart, D. 1850. The Pillars of Hercules. Harper and Brothers, New York.